1 Session 1: Introduction and setup

1.1 Reproducible Research, RStudio and Git/GitHub Setup

1.1.1 Learning Objectives

In this lesson, you will learn:

- Why reproducibility in research is useful

- What is meant by computational reproducibility

- How to check to make sure your RStudio environment is set up properly for analysis

- How to set up git

1.1.2 Introduction to reproducible research

Reproducibility is the hallmark of science, which is based on empirical observations coupled with explanatory models. And reproducible research is at the core of what we do at NCEAS, research synthesis.

The National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis was funded over 25 years ago to bring together interdisciplinary researchers in exploration of grand challenge ecological questions through analysis of existing data. Such questions often require integration, analysis and synthesis of diverse data across broad temporal, spatial and geographic scales. Data that is not typically collected by a single individual or collaborative team. Synthesis science, leveraging previously collected data, was a novel concept at that time and the approach and success of NCEAS has been a model for other synthesis centers.

During this course you will learn about some of the challenges that can be encountered when working with published data, but more importantly, how to apply best practices to data collection, documentation, analysis and management to mitigate these challenges in support of reproducible research.

During this course you will learn about some of the challenges that can be encountered when working with published data, but more importantly, how to apply best practices to data collection, documentation, analysis and management to mitigate these challenges in support of reproducible research.

Why is reproducible research important?

Working in a reproducible manner builds efficiencies into your own research practices. The ability to automate processes and rerun analyses as you collect more data, or share your full workflow (including data, code and products) with colleagues, will accelerate the pace of your research and collaborations. However, beyond these direct benefits, reproducible research builds trust in science with the public, policy makers and others.

What data were used in this study? What methods applied? What were the parameter settings? What documentation or code are available to us to evaluate the results? Can we trust these data and methods?

Are the results reproducible?

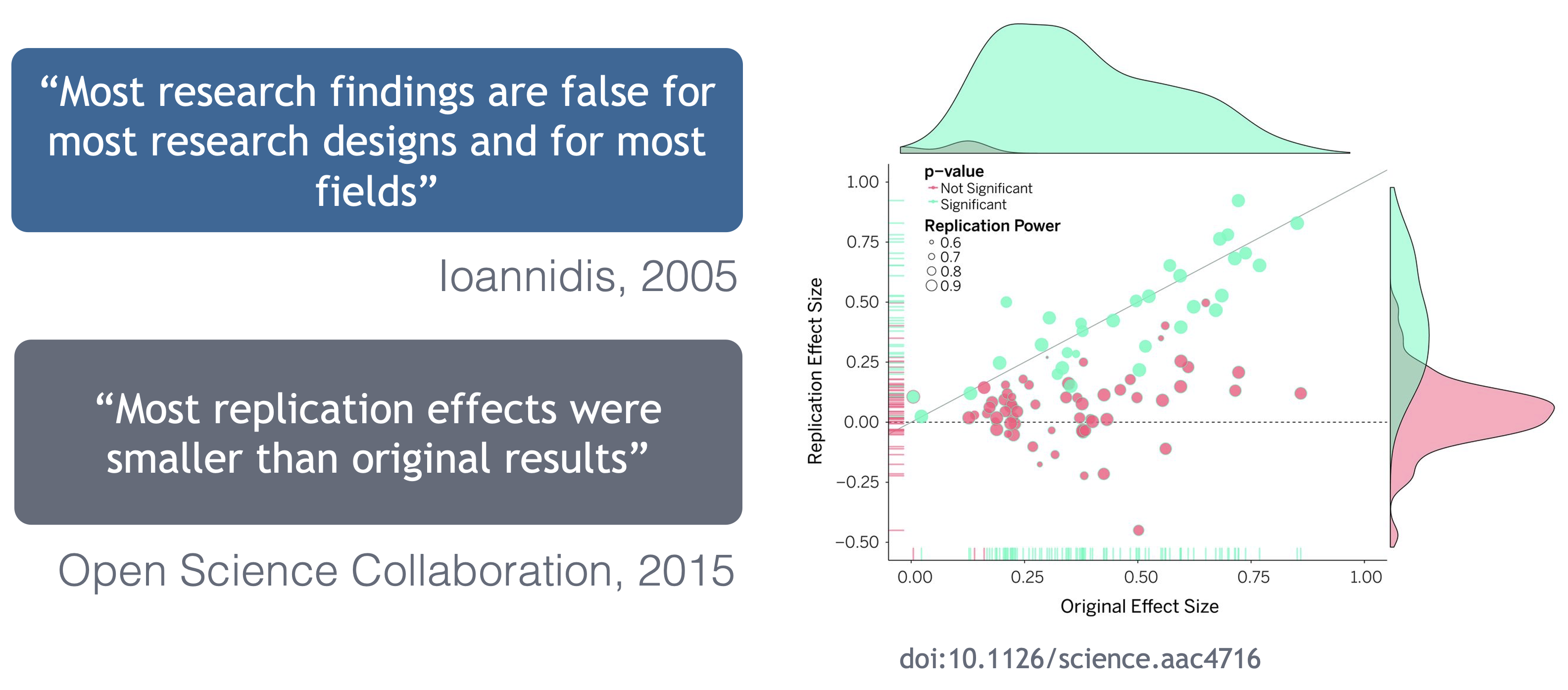

Ionnidis (2005) contends that “Most research findings are false for most research designs and for most fields”, and a study of replicability in psychology experiments found that “Most replication effects were smaller than the original results” (Open Science Collaboration, 2015).

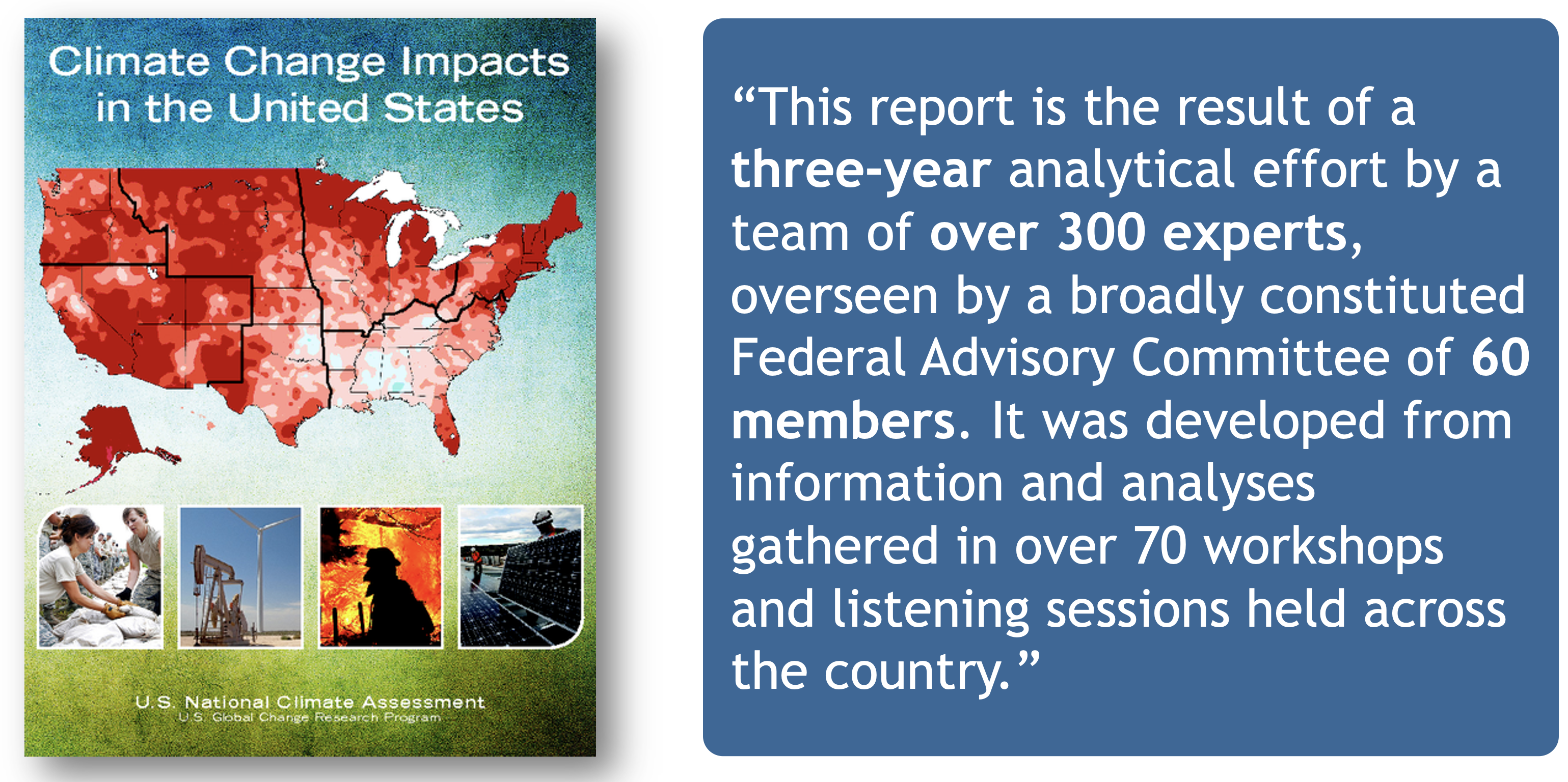

In the case of ‘climategate’, it took three years, and over 300 personnel, to gather the necessary provenance information in order to document how results, figures and other outputs were derived from input sources. Time and effort that could have been significantly reduced with appropriate documentation and reproducible practices. Moving forward, through reproducible research training, practices, and infrastructure, the need to manually chase this information will be reduced enabling replication studies and great trust in science.

Computational reproducibility

While reproducibility encompasses the full science lifecycle, and includes issues such as methodological consistency and treatment of bias, in this course we will focus on computational reproducibility: the ability to document data, analyses, and models sufficiently for other researchers to be able to understand and ideally re-execute the computations that led to scientific results and conclusions.

The first step towards addressing these issues is to be able to evaluate the data, analyses, and models on which conclusions are drawn. Under current practice, this can be difficult because data are typically unavailable, the method sections of papers do not detail the computational approaches used, and analyses and models are often conducted in graphical programs, or, when scripted analyses are employed, the code is not available.

And yet, this is easily remedied. Researchers can achieve computational reproducibility through open science approaches, including straightforward steps for archiving data and code openly along with the scientific workflows describing the provenance of scientific results (e.g., Hampton et al. (2015), Munafò et al. (2017)).

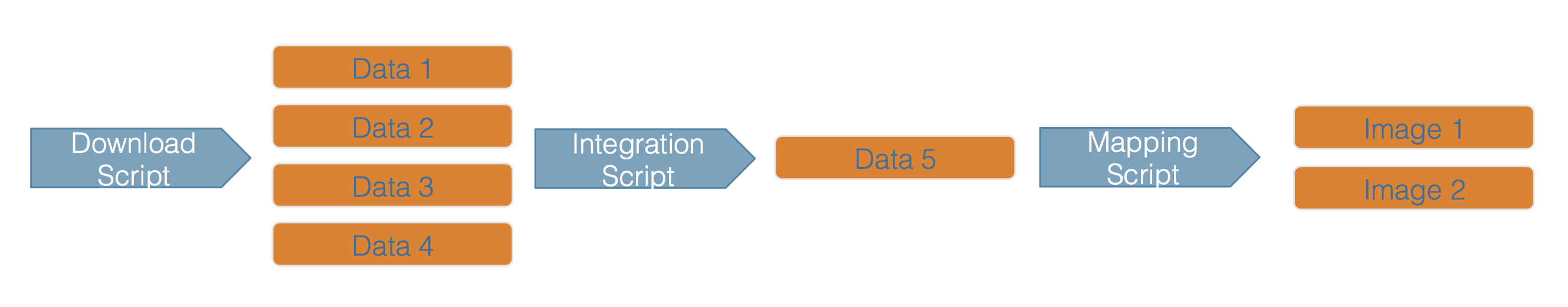

Conceptualizing workflows

Scientific workflows encapsulate all of the steps from data acquisition, cleaning, transformation, integration, analysis, and visualization.

Workflows can range in detail from simple flowcharts to fully executable scripts. R scripts and python scripts are a textual form of a workflow, and when researchers publish specific versions of the scripts and data used in an analysis, it becomes far easier to repeat their computations and understand the provenance of their conclusions.

1.1.2.1 Summary

Computational reproducibility provides:

- transparency by capturing and communicating scientific workflows

- research to stand on the shoulders of giants (build on work that came before)

- credit for secondary usage and supports easy attribution

- increased trust in science

Preserving computational workflows enables understanding, evaluation, and reuse for the benefit of future you and your collaborators and colleagues across disciplines.

Reproducibility means different things to different researchers. For our purposes, practical reproducibility looks like:

- Preserving the data

- Preserving the software workflow

- Documenting what you did

- Describing how to interpret it all

During this course will outline best practices for how to make those four components happen.

1.1.3 Logging into the RStudio server

To help prevent us from spending most of this lesson remotely troubleshooting the myriad of issues that can arise when setting up the R, RStudio, and git environments, we have chosen to have everyone work on a remote server with all of the software you need installed. We will be using a special kind of RStudio just for servers called, aptly, RStudio Server. If you have never worked on a remove server before, you can think of it like working on a different computer via the internet. Note that the server has no knowledge of the files on your local filesystem, but it is easy to transfer files from the server to your local computer, and vice-versa, using the RStudio server interface.

Here are the instructions for logging in and getting set up:

Setup

You should have received an email prompting you to change your password for your server account. If you did not, please let one of the helpers know on Slack.

If you were able to successfully change your password, you can log in at: https://included-crab.nceas.ucsb.edu/

In this workshop, we are going to be using R projects to organize our work. An R project is tied to a directory on your local computer, and makes organizing your work and collaborating with others easier.

We are going to be doing nearly all of the work in this course in one project. Our version of RStudio server allows you to share projects with others. Sharing your project with the instructors of the course will allow for them to jump into your session and type along with you, should you encounter an error you cannot fix.

Setup

In your RStudio server session, follow these steps to set up your shared project:

- In the “File” menu, select “New Project”

- Click “New Directory”

- Click “New Project”

- Under “Directory name” type:

training_{USERNAME}, eg:training_jclark - Leave “Create Project as subdirectory of:” set to

~ - Click “Create Project”

Your Rstudio should now open your project. To share your project with the instructor team, locate the “project switcher” dropdown menu in the upper right of your RStudio window. This dropdown has the name if your project (eg: training_clark), and a dropdown arrow. Click the dropdown menu, then “Share Project.” When the dialog box pops up, add the following usernames to your project:

- jclark

- mecum

- jasminelai

- aebudden

Once those names show up in the list, click “OK”.

Setting up git

If you haven’t already, go to github.com and create an account.

Before using git, you need to tell it who you are, also known as setting the global options. The only way to do this is through the command line. Newer versions of RStudio have a nice feature where you can open a terminal window in your RStudio session. Do this by selecting Tools -> Terminal -> New Terminal.

A terminal tab should now be open where your console usually is.

To see if you aleady have your name and email options set, use this command from the terminal:

To set the global options, type the following into the command prompt, with your actual name, and press enter:

Next, enter the following line, with the email address you used when you created your account on github.com:

Note that these lines need to be run one at a time.

Finally, check to make sure everything looks correct by entering these commands, which will return the options that you have set.

1.1.4 Setting up the R environment on your local computer

Even though we have you working on a remote server, we still recommend that you set up your own computer with the following software so that you are ready to take the tools you learn in the course into your daily work.

R Version

We will use R version 4.0.2, which you can download and install from CRAN. To check your version, run this in your RStudio console:

If you have R version 4.0.0 that will likely work fine as well.

RStudio Version

We will be using RStudio version 1.3.1000 or later, which you can download and install here To check your RStudio version, run the following in your RStudio console:

If the output of this does not say 1.2.500 or higher, you should update your RStudio. Do this by selecting Help -> Check for Updates and follow the prompts.

Package installation

Run the following lines to check that all of the packages we need for the training are installed on your computer.

packages <- c("dplyr", "tidyr", "readr", "devtools", "usethis", "roxygen2", "leaflet", "ggplot2", "DT", "scales", "shiny", "sf", "ggmap", "broom", "captioner", "MASS")

for (package in packages) { if (!(package %in% installed.packages())) { install.packages(package) } }

rm(packages) #remove variable from workspace

# Now upgrade any out-of-date packages

update.packages(ask=FALSE)If you haven’t installed all of the packages, this will automatically start installing them. If they are installed, it won’t do anything.

Next, create a new R Markdown (File -> New File -> R Markdown). If you have never made an R Markdown document before, a dialog box will pop up asking if you wish to install the required packages. Click yes.

At this point, RStudio and R should be all set up.

Setting up git locally

Every time you set up git on a new computer, the steps we took above to set up git are required. See the above section on setting up git to set your git username and email address.

Note for Windows Users

If you get “command not found” (or similar) when you try these steps through the RStudio terminal tab, you may need to set the type of terminal that gets launched by RStudio. Under some git install scenarios, the git executable may not be available to the default terminal type. Follow the instructions on the RStudio site for Windows specific terminal options. In particular, you should choose “New Terminals open with Git Bash” in the Terminal options (Tools->Global Options->Terminal).

In addition, some versions of windows have difficulty with the command line if you are using an account name with spaces in it (such as “Matt Jones”, rather than something like “mbjones”). You may need to use an account name without spaces.

Updating a previous R installation

This is useful for users who already have R with some packages installed and need to upgrade R, but don’t want to lose packages. If you have never installed R or any R packages before, you can skip this section.

If you already have R installed, but need to update, and don’t want to lose your packages, these two R functions can help you. The first will save all of your packages to a file. The second loads the packages from the file and installs packages that are missing.

Save this script to a file (eg package_update.R).

#' Save R packages to a file. Useful when updating R version

#'

#' @param path path to rda file to save packages to. eg: installed_old.rda

save_packages <- function(path){

tmp <- installed.packages()

installedpkgs <- as.vector(tmp[is.na(tmp[,"Priority"]), 1])

save(installedpkgs, file = path)

}

#' Update packages from a file. Useful when updating R version

#'

#' @param path path to rda file where packages were saved

update_packages <- function(path){

tmp <- new.env()

installedpkgs <- load(file = path, envir = tmp)

installedpkgs <- tmp[[ls(tmp)[1]]]

tmp <- installed.packages()

installedpkgs.new <- as.vector(tmp[is.na(tmp[,"Priority"]), 1])

missing <- setdiff(installedpkgs, installedpkgs.new)

install.packages(missing)

update.packages(ask=FALSE)

}Source the file that you saved above (eg: source(package_update.R)). Then, run the save_packages function.

Then quit R, go to CRAN, and install the latest version of R.

Source the R script that you saved above again (eg: source(package_update.R)), and then run:

This should install all of your R packages that you had before you upgraded.

References

Hampton, Stephanie E, Sean Anderson, Sarah C Bagby, Corinna Gries, Xueying Han, Edmund Hart, Matthew B Jones, et al. 2015. “The Tao of Open Science for Ecology.” Ecosphere 6 (July). https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.1890/ES14-00402.1.

Munafò, Marcus R., Brian A. Nosek, Dorothy V. M. Bishop, Katherine S. Button, Christopher D. Chambers, Nathalie Percie du Sert, Uri Simonsohn, Eric-Jan Wagenmakers, Jennifer J. Ware, and John P. A. Ioannidis. 2017. “A Manifesto for Reproducible Science.” Nature Human Behaviour 1 (1): 0021. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-016-0021.