8 Data Ethics

8.1 Open Data Ethics

Developed in collaboration with the Exchange for Local Observations and Knowledge of the Arctic (ELOKA) and Navigating the New Arctic Community Office (NNA-CO).

8.1.1 Learning Objectives

In this lesson, we will:

- Discuss Indigenous Data Sovereignty in the context of open science

- Discuss FAIR and CARE Principles

- Examine case studies of relationships between Arctic Indigenous communities and natural science researchers

8.1.2 Ethical Data Considerations in Your Research

As the primary repository for the Arctic program of the National Science Foundation, the Arctic Data Center accepts Arctic data from all disciplines. Recently, a new submission feature was released which asks researchers to describe the ethical considerations that are apparent in their research. This question is asked to all researchers, regardless of disciplines.

8.1.2.1 Discussion Questions

- Before diving into the world of ethics, what ethical concerns do you consider in your research?

- Please fill out this form to briefly describe any ethical concerns apparent in the research you conduct: https://forms.gle/VcogEPwcgVfnEj9f7

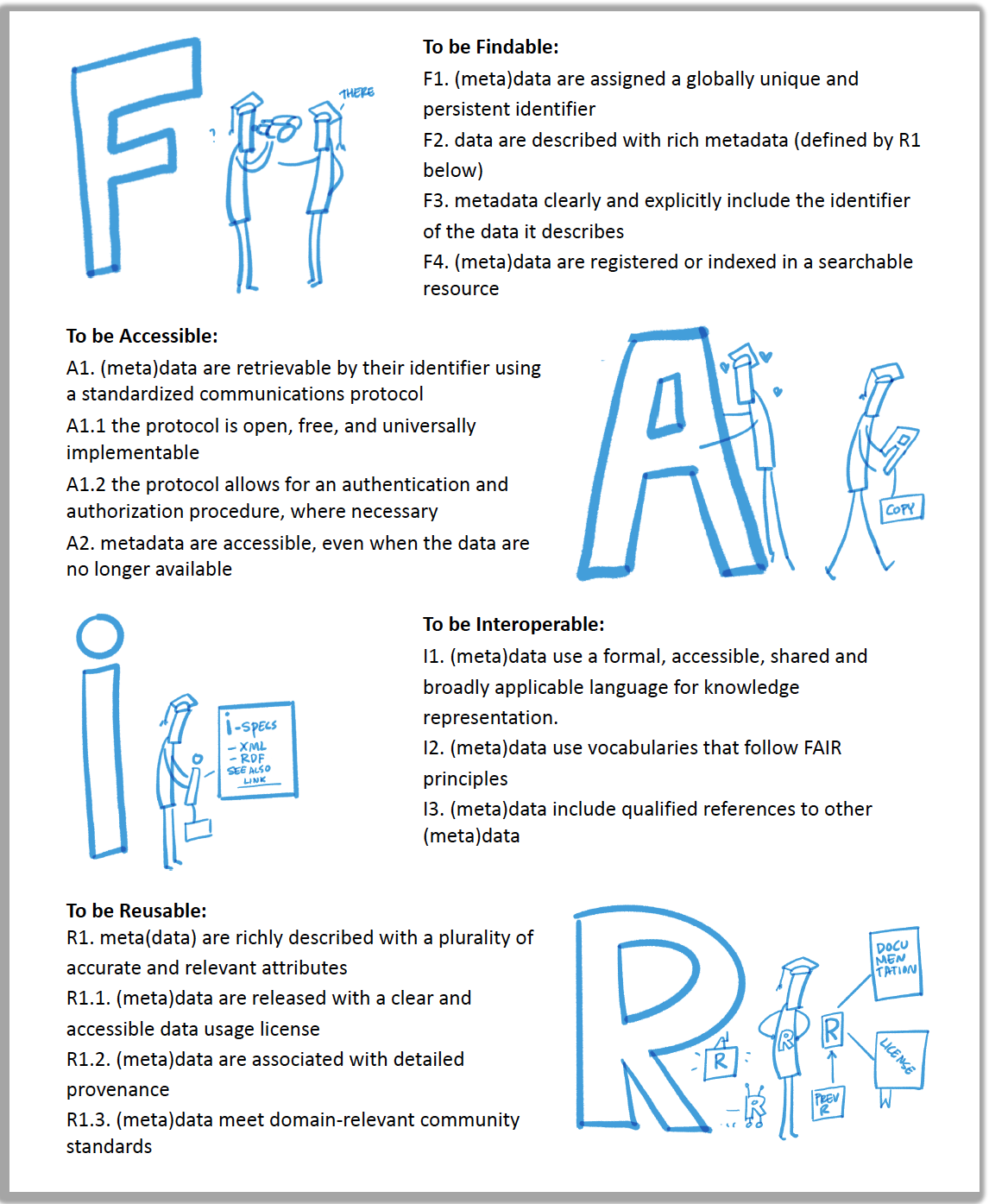

8.1.3 FAIR and Open Science

To recap, the Arctic Data Center is an openly-accessible data repository and the data published through the repository is open for anyone to reuse, subject to conditions of the license (at the Arctic Data Center, data is released under one of two licenses: CC-0 Public Domain and CC-By Attribution 4.0). In facilitating use of data resources, the data stewardship community have converged on principles surrounding best practices for open data management One set of these principles is the FAIR principles. FAIR stands for Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reproducible.

The FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reproducible) principles for data management are widely known and broadly endorsed.

FAIR Principles and open science are not synonymous, however they often go hand in hand. However, data can be open and not FAIR, and vice verse.

FAIR Principles and open science are not synonymous, however they often go hand in hand. However, data can be open and not FAIR, and vice verse.

The “Fostering FAIR Data Practices in Europe” project found that it is more monetarily and timely expensive when FAIR principles are not used, and it was estimated that 10.2 billion dollars per years are spent through “storage and license costs to more qualitative costs related to the time spent by researchers on creation, collection and management of data, and the risks of research duplication.”

FAIR principles and open science are overlapping concepts, but are distinctive concepts. Open science supports a culture of sharing research outputs and data, and FAIR focuses on how to prepare the data. The FAIR principles place emphasis on machine readability, “distinct from peer initiatives that focus on the human scholar” (Wilkinson et al 2016) and as such, do not fully engage with sensitive data considerations and with Indigenous rights and interests (Research Data Alliance International Indigenous Data Sovereignty Interest Group, 2019). Research has historically perpetuated colonialism and represented extractive practices, meaning that the research results were not mutually beneficial. These issues also related to how data was owned, shared, and used.

To address issues like these, the Global Indigenous Data Alliance (GIDA) introduced CARE Principles for Indigenous Data Governance to support Indigenous data sovereignty. CARE Principles for Indigenous Data Governance stand for Collective Benefit, Authority to Control, Responsibility, Ethics. The CARE principles for Indigenous Data Governance complement the more data-centric approach of the FAIR principles, introducing social responsibility to open data management practices. These principles ask researchers to put human well-being at the forefront of open-science and data sharing (Carroll et al., 2021; Research Data Alliance International Indigenous Data Sovereignty Interest Group, September 2019). Indigenous data sovereignty and considerations related to working with Indigenous communities are particularly relevant to the Arctic. The CARE Principles stand for:

- Collective Benefit - Data ecosystems shall be designed and function in ways that enable Indigenous Peoples to derive benefit from the data

- Authority to Control - Indigenous Peoples’ rights and interests in Indigenous data must be recognized and their authority to control such data be empowered. Indigenous data governance enables Indigenous Peoples and governing bodies to determine how Indigenous Peoples, as well as Indigenous lands, territories, resources, knowledges and geographical indicators, are represented and identified within data.

- Responsibility - Those working with Indigenous data have a responsibility to share how those data are used to support Indigenous Peoples’ self-determination and collective benefit. Accountability requires meaningful and openly available evidence of these efforts and the benefits accruing to Indigenous Peoples.

- Ethics - Indigenous Peoples’ rights and wellbeing should be the primary concern at all stages of the data life cycle and across the data ecosystem.

To many, the FAIR and CARE principles are viewed by many as complementary: CARE aligns with FAIR by outlining guidelines for publishing data that contributes to open-science and at the same time, accounts for Indigenous’ Peoples rights and interests.

Sharing sensitive data introduces unique ethical considerations, and FAIR and CARE principles speak to this by recommending sharing anonymized metadata to encourage discover ability and reduce duplicate research efforts, following consent of rights holders (Puebla & Lowenberg, 2021). While initially designed to support Indigenous data sovereignty, CARE principles are being adopted more broadly and researchers argue they are relevant across all disciplines (Carroll et al., 2021). As such, these principles introduce a “game changing perspective” for all researchers that encourages transparency in data ethics, and encourages data reuse that is both purposeful and intentional and that aligns with human well-being (Carroll et al., 2021). Hence, to enable the research community to articulate and document the degree of data sensitivity, and ethical research practices, the Arctic Data Center has introduced new submission requirements.

8.2 Discussion questions:

- What main differences between the two case studies stand out to you?

- What data ethics do you consider in your research? Why or why not?

- How do you see CARE and FAIR principles working together?

- How do you see Indigenous data sovereignty working in the context of open science?

8.3 Data Ethics Resources

8.3.0.1 Resources

Trainings:

Fundamentals of OCAP (online training - for working with First Nations in Canada): https://fnigc.ca/ocap-training/take-the-course/

Native Nations Institute trainings on Indigenous Data Sovereignty and Indigenous Data Governance: https://igp.arizona.edu/jit

The Alaska Indigenous Research Program, is a collaboration between the Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium (ANTHC) and Alaska Pacific University (APU) to increase capacity for conducting culturally responsive and respectful health research that addresses the unique settings and health needs of Alaska Native and American Indian People. The 2022 program runs for three weeks (May 2 - May 20), with specific topics covered each week. Week two (Research Ethics) may be of particular interest. Registration is free.

The r-ETHICS training (Ethics Training for Health in Indigenous Communities Study) is starting to become an acceptable, recognizable CITI addition for IRB training by tribal entities.

Kawerak, Inc and First Alaskans Institute have offered trainings in research ethics and Indigenous Data Sovereignty. Keep an eye out for further opportunities from these Alaska-based organizations.

On open science and ethics:

ON-MERRIT recommendations for maximizing equity in open and responsible research https://zenodo.org/record/6276753#.YjjgC3XMLCI

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10677-019-10053-3

https://sagebionetworks.org/in-the-news/on-the-ethics-of-open-science-2/

Arctic social science and data management:

Arctic Horizons report: Anderson, S., Strawhacker, C., Presnall, A., et al. (2018). Arctic Horizons: Final Report. Washington D.C.: Jefferson Institute. https://www.jeffersoninst.org/sites/default/files/Arctic%20Horizons%20Final%20Report%281%29.pdf

Arctic Data Center workshop report: https://arcticdata.io/social-scientific-data-workshop/

Arctic Indigenous research and knowledge sovereignty frameworks, strategies and reports:

Kawerak, Inc. (2021) Knowledge & Research Sovereignty Workshop May 18-21, 2021 Workshop Report. Prepared by Sandhill.Culture. Craft and Kawerak Inc. Social Science Program. Nome, Alaska.

Inuit Circumpolar Council. 2021. Ethical and Equitable Engagement Synthesis Report: A collection of Inuit rules, guidelines, protocols, and values for the engagement of Inuit Communities and Indigenous Knowledge from Across Inuit Nunaat. Synthesis Report. International.

Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami. 2018. National Inuit Strategy on Research. Accessed at: https://www.inuitcircumpolar.com/project/icc-ethical-and-equitable-engagement-synthesis-report/

Indigenous Data Governance and Sovereignty:

McBride, K. Data Resources and Challenges for First Nations Communities. Document Review and Position Paper. Prepared for the Alberta First Nations Information Governance Centre.

Carroll, S.R., Garba, I., Figueroa-Rodríguez, O.L., Holbrook, J., Lovett, R., Materechera, S., Parsons, M., Raseroka, K., Rodriguez-Lonebear, D., Rowe, R., Sara, R., Walker, J.D., Anderson, J. and Hudson, M., 2020. The CARE Principles for Indigenous Data Governance. Data Science Journal, 19(1), p.43. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5334/dsj-2020-043

Kornei, K. (2021), Academic citations evolve to include Indigenous oral teachings, Eos, 102, https://doi.org/10.1029/2021EO210595. Published on 9 November 2021.

Kukutai, T. & Taylor, J. (Eds.). (2016). Indigenous data sovereignty: Toward an agenda. Canberra: Australian National University Press. See the editors’ Introduction and Chapter 7.

Kukutai, T. & Walter, M. (2015). Indigenising statistics: Meeting in the recognition space. Statistical Journal of the IAOS, 31(2), 317–326.

Miaim nayri Wingara Indigenous Data Sovereignty Collective and the Australian Indigenous Governance Institute. (2018). Indigenous data sovereignty communique. Indigenous Data Sovereignty Summit, 20 June 2018, Canberra. http://www.aigi.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Communique-Indigenous-Data-Sovereignty-Summit.pdf

National Congress of American Indians. (2018). Resolution KAN-18-011: Support of US Indigenous data sovereignty and inclusion of tribes in the development of tribal data governance principles. http://www.ncai.org/attachments/Resolution_gbuJbEHWpkOgcwCICRtgMJHMsUNofqYvuMSnzLFzOdxBlMlRjij_KAN-18-011%20Final.pdf

Rainie, S., Kukutai, T., Walter, M., Figueroa-Rodriguez, O., Walker, J., & Axelsson, P. (2019) Issues in Open Data - Indigenous Data Sovereignty. In T. Davies, S. Walker, M. Rubinstein, & F. Perini (Eds.), The State of Open Data: Histories and Horizons. Cape Town and Ottawa: African Minds and International Development Research Centre. https://zenodo.org/record/2677801#.YjqOFDfMLPY

Schultz, Jennifer Lee, and Stephanie Carroll Rainie. 2014. “The Strategic Power of Data : A Key Aspect of Sovereignty.” 5(4).

Trudgett, Skye, Kalinda Griffiths, Sara Farnbach, and Anthony Shakeshaft. 2022. “A Framework for Operationalising Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Data Sovereignty in Australia: Results of a Systematic Literature Review of Published Studies.” eClinicalMedicine 45: 1–23.

IRBs/Tribal IRBs:

Around Him D, Aguilar TA, Frederick A, Larsen H, Seiber M, Angal J. Tribal IRBs: A Framework for Understanding Research Oversight in American Indian and Alaska Native Communities. Am Indian Alsk Native Ment Health Res. 2019;26(2):71-95. doi: 10.5820/aian.2602.2019.71. PMID: 31550379.

Kuhn NS, Parker M, Lefthand-Begay C. Indigenous Research Ethics Requirements: An Examination of Six Tribal Institutional Review Board Applications and Processes in the United States. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics. 2020;15(4):279-291. doi:10.1177/1556264620912103

Marley TL. Indigenous Data Sovereignty: University Institutional Review Board Policies and Guidelines and Research with American Indian and Alaska Native Communities. American Behavioral Scientist. 2019;63(6):722-742. doi:10.1177/0002764218799130

Marley TL. Indigenous Data Sovereignty: University Institutional Review Board Policies and Guidelines and Research with American Indian and Alaska Native Communities. American Behavioral Scientist. 2019;63(6):722-742. doi:10.1177/0002764218799130

Ethical research with Sami communities:

Eriksen, H., Rautio, A., Johnson, R. et al. Ethical considerations for community-based participatory research with Sami communities in North Finland. Ambio 50, 1222–1236 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-020-01459-w

Jonsson, Å.N. Ethical guidelines for the documentation of árbediehtu, Sami traditional knowledge. In Working with Traditional Knowledge: Communities, Institutions, Information Systems, Law and Ethics. Writings from the Árbediehtu Pilot Project on Documentation and Protection of Sami Traditional Knowledge. Dieđut 1/2011. Sámi allaskuvla / Sámi University College 2011: 97–125. https://samas.brage.unit.no/samas-xmlui/bitstream/handle/11250/177065/Diedut-1-2011_AasaNordinJonsson.pdf?sequence=8&isAllowed=y