Learning Objectives

- Provide tools to navigate the social aspects of collaboration

- Discuss collaboration best practices

- Explore key aspects of the science of team science

Most of this lesson comes from information written by NCEAS Senior Fellow Carrie Kappel on NCEAS Guidance for Collaborative Synthesis Science Working Groups. Carrie is an expert team science facilitator.

2.1 Successful synthesis science working groups

Based on NCEAS experience doing synthesis science and guiding hundreds of working groups, here are some aspects successful groups have in common. It is important to know that there is no on-size-fits-all recipe that works for every group, but there are some key ingredients that NCEAS have seen confer success over and over.

Exciting synthesis science questions linked to impact: Novel synthesis of existing data with high likelihood of contributing solutions to pressing problems.

Diverse participants: Gender, ethnicity, geographic-origin, sector, discipline, age, job function and career stage

Effective leadership to spark a creative vision, facilitate an inclusive process, and provide effective project management to maintain momentum and deliver on objectives.

Data access and management: Working group members identify and access rich datasets, integrate data management into work plan, and apply best practices for open, reproducible science

Well-developed work plan takes advantage of the group’s diverse talents, interests, and incentives, with clear milestones, deliverables, and assigned responsibilities

Justified methods and logical links: Data collection and analytical methods, metrics, and models based on a solid understanding of the existing literature

Good communication and collaboration: Establish mutually agreed upon norms and systems

Social bonding and team cohesion: Spend time together as a groups on different settings, not only working towards the project’s goal.

2.2 Creating a Culture of Collaboration

The over all goal of this Seminar Series is to equip you with data science and team science tools, providing a platform to conduct collaborative synthesis research. Collaboration is defined as: “the action of working with someone to produce or create something”, in this case synthesis research. In order for collaboration to be successful and enjoyable experience we need to foster a good collaboration culture.

Key elements to a good collaboration culture:

Norms and expectations: Defining how collaborators want to engage with each other, how conflicts should be handled and how credit will be shared and attributed.

Data sharing and authorship responsibilities: Given the diverse fields and sectors represented in synthesis working groups, members may have divergent perspectives around credit and data sharing. These should be discussed early and often. The International Committee of Medical Journal Editors guidelines for authorship and contribution are a good starting place.

Equal opportunities for participation: Members need an opportunity to share and be recognized for their expertise early in the process, so build in time for informative introductions (e.g., lightning presentations or round-robin introductions accompanied by circulated written bios). Consider creating the opportunity for learning proper spelling and pronunciation of group members’ names and requiring participants to also indicate their pronouns.

Sharing facilitation responsibilities: Each activity should have an objective. The duty of keeping the group on track toward those objectives can be rotated.

2.2.1 Norms and Expectations: Developing a code of conduct

Whether you are joining a lab group or establishing a new collaboration, articulating a set of shared agreements about how people in the group will treat each other will help create the conditions for successful collaboration. If agreements or a code of conduct do not yet exist, invite a conversation among all members to create them. Co-creation of a code of conduct will foster collaboration and engagement as a process in and of itself, and is important to ensure all voices heard such that your code of conduct represents the perspectives of your community. If a code of conduct already exists, and your community will be a long-acting collaboration, you might consider revising the code of conduct. Having your group ‘sign off’ on the code of conduct, whether revised or not, supports adoption of the principles.

When creating a code of conduct, consider both the behaviors you want to encourage and those that will not be tolerated. For example, the Openscapes code of conduct includes Be respectful, honest, inclusive, accommodating, appreciative, and open to learning from everyone else. Do not attack, demean, disrupt, harass, or threaten others or encourage such behavior.

Below are other example codes of conduct:

2.3 Team Communication

Defining the ground rules of how your team is going to operates is a great starting We are now going to talk about communicating with each other in a positive and productive way to enhance the group’s work, including all voices and making sure conflicts and disagreements are addressed.

2.3.1 Moving from debate to dialogue

Synthesis working groups often convene diverse collections of participants not otherwise collaborating to catalyze novel insights and solutions. One primary method of catalyzing novel ideas is to allow the flow of dialogue during a group meeting. In contrast to debate or discussion, dialogue allows groups to recognize the limits on their own and others’ individual perspectives and to strive for more coherent thought. This process can take working groups in directions not imagined or planned.

In discussion, different views are presented and defended, and this may provide a useful analysis of the whole situation. In dialogue, all views are treated as equally valid and different views are presented as a means toward discovering a new view. In a skillful discussion, decisions are made. In a dialogue, complex issues are explored. Both are critical to the working group process, and the more artfully a group can move between these two forms of discourse (and out of less productive debate and polite discussion) according to what is needed, the more effective the group will be.

2.3.2 Embracing divergent thinking

The most important outcome of your first meeting is getting convergence or group alignment on a set of shared goals and objectives and a plan for how to achieve them. If your working group process is effective, this plan will be an inclusive solution – one that works for everyone in the group. Achieving this shared vision can be more difficult than one might expect. While you may expect that participants have already agreed to the vision in joining the group, agreement does not always equate to alignment.

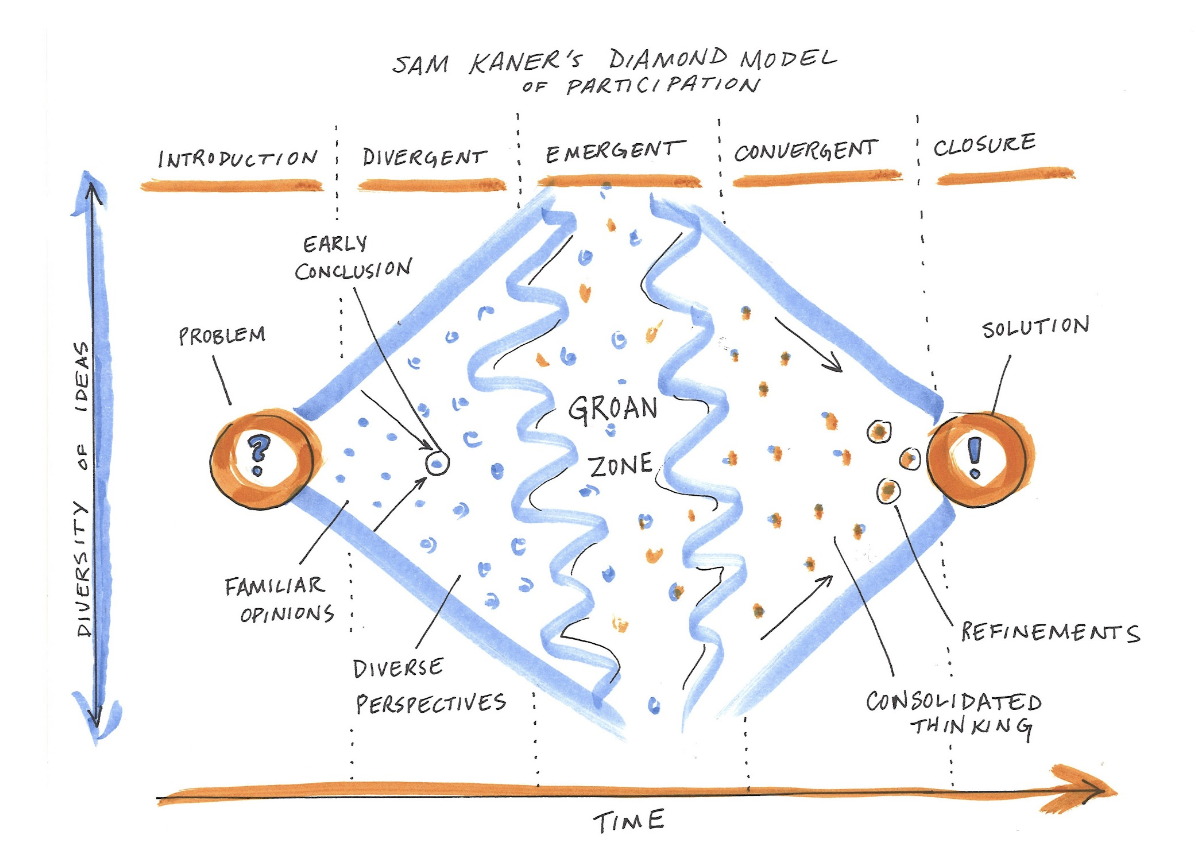

When a diverse group comes together to work on a complex problem, their views are likely to diverge widely across many dimensions from problem definition to priorities to methods/approaches to the definition of success. But you can tap that divergent thinking to generate entirely new ideas and options that emerge through the group’s productive struggle for mutual understanding.

The first stage of group decision-making is divergent thinking (Kaner et al. 2014 ). Confronted with a new, complex topic, the group will gradually move from the safe territory of familiar opinions into sharing their diverse perspectives and exploring new ideas. This can feel like the group process is devolving away from what was assumed to be shared agreement, but it is actually a critical part of the collaborative process.

While a group is in the divergent thinking stage, it’s critical to:

Foster dialogue to surface different perspectives.

Examine hidden assumptions.

Create room for disagreement and questioning.

Amplify diverse perspectives in order to expand the range of possibilities.

Suspend judgment and encourage full participation.

Useful facilitation techniques at this stage include:

| Technique | Description |

|---|---|

| Brainstorm | Collect lots of ideas, verbally and/or with sticky notes |

| Breakout groups | Mix up participation and allow parallel generation of ideas |

| Prompts and homework | To encourage deeper, out of the box thinking |

| Round robins | To get starting positions out on the table |

| Informal & spontaneous interaction | Water cooler, take a (coffee) break, or other casual conversation opportunities |

| Engage diverse perspectives | Encouraging and drawing out people, mirroring and validating what they say, and really honor their contributions |

| Come at your problem from multiple angles | Build on different ideas |

If participants do not feel like the working group climate allows for critical inquiry, they may agree to the aims on the surface, but latent questions and disagreements will linger underneath. If those latent concerns persist, the work will suffer in the long run. While it may feel like there is agreement in that case, the group lacks alignment, and the effort is unlikely to successfully meet its goals.

2.3.3 Between divergent thinking and convergence: the groan zone

It’s natural for groups to go through a period of confusion and frustration as they struggle to integrate their diverse perspectives into a shared framework of understanding (Kaner et al. 2014 ). The goal is to get the group across this no man’s land between divergent thinking and convergence known as the “groan zone.” In the groan zone, one importat thing is to keep the group from getting frustrated and shutting down. Some useful techniques for the groan zone include:

- Separating facts and opinions

- Creating categories to reveal structure and allow sorting and prioritization

- Carefully examining language, e.g. by looking word by word at a key statement or question that is being debated and asking what questions each word raises

- Creating a parking lot to capture side issues and reserving time to revisit these – taking the tangents seriously is a critical part of letting participants know you value their contributions

- Examining how proposed ideas might affect each individual in the group

- Honoring objections to the process and asking for suggestions

If the conversation is getting off track or the dynamics becomes difficult, useful techniques that allow “the leader” or facilitator to remain committed to being supportive and respectful of all group members (including “difficult” ones) are:

- Reminding individuals of the larger purpose of the group and reconnecting them to their own personal reasons for caring about and working on the issue, e.g. by inviting them to take a moment to reflect

- Taking a break

- Switching the participation format (e.g., going to breakout groups, brainstorming, a go-around, or individual writing)

- Stepping out of the content and addressing the process

- Educating members about group dynamics

- Encouraging more people to participate

- Reframing the discussion, e.g. by surfacing underlying issues, and/or focusing on concrete actions that the group can take to resolve the conflict

- Focusing on common ground and areas of potential alignment

Don’t get discouraged by the groan zone. Remember that misunderstanding and miscommunication are normal parts of the process. And even more importantly, “the act of working through these misunderstandings is what builds the foundation for sustainable agreements and meaningful collaboration” (Kaner et al. 2014 ).

2.3.4 Getting to convergence

Once the group has a strong foundation of shared understanding, things start to click into place and everything will feel easier and faster as you enter the zone of convergent thinking. At this point, the group is ready to devise inclusive solutions, weigh alternatives and make decisions. The goal on this step is to help the group devise specific proposals, evaluate and decide among them, and refine and synthesize into an overall approach, and lay out a concrete plan.

Techniques that are useful in this phase include:

- Pulling up examples for inspiration

- Invite participants to make clear verbal or written proposals

- Creative reframing to support more innovative, inclusive solutions

- Chart writing and summarizing so that participants can see their ideas in writing and refine them

- Clarify areas of agreement and disagreement

- Decide how you are going to make decisions and have a fallback plan

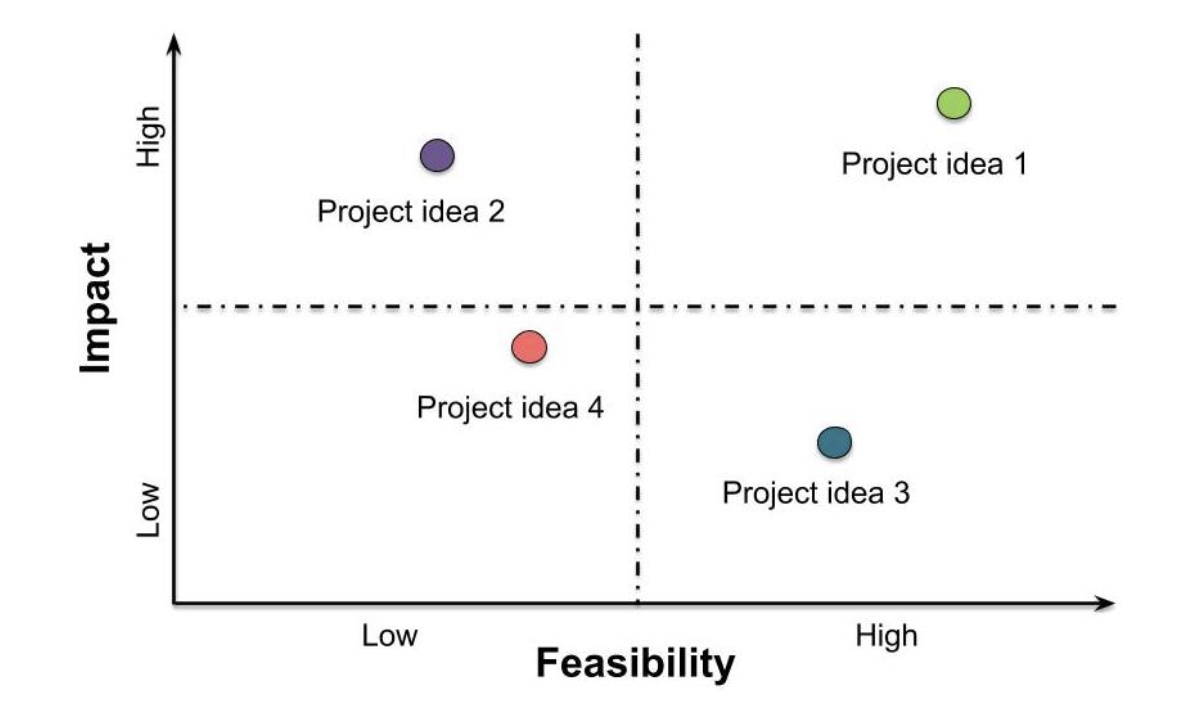

- Evaluating alternatives along the axes of feasibility and impact to identify the options that are both high impact and highly feasible. Another useful comparison may be payoffs and risks. Be sure to define what you mean by each axis before you start evaluating ideas.

- Planning the work flow, using a timetable, Gantt chart, or other tool

- Defining steps and milestones

- Capturing who does what, by when – For each deliverable, identify the person(s):

- Responsible (the lead on a deliverable)

- Accountable (those who will contribute)

- Consulted (those who may be asked for advice), and

- Informed (those who just want to be kept in the loop)

While the big first step in synthesis is getting to convergence on the overall work plan, you should expect that the group may have to go through mini versions of the process of divergence and convergence again in future meetings as they dive into the work and uncover new challenges. But the shared understanding and social rapport that come from successfully struggling together early on will allow the group to more easily and rapidly develop and implement new solutions in subsequent meetings.

2.4 The Power of Open

Adopting an open source mindset, tools, and communication channels can increase the efficiency of your team’s analyses, their impact, and reach. Furthermore establishing good collaboration practices can transform the culture of how we do science. This means enabling an open culture driven by collaboration, empathy, and kindness. Strengthening collaboration, leading teams to be more efficient and positive.

- Check out the paper Our path to better science in less time using open data science tools in Nature Ecology & Evolution, led by Openscapes founder and NCEAS Senior Fellow, Julia Lowndes, for an example of how empowering these open workflows can be for research teams.

2.5 Activity

- Developing a code of conduct

- Set of shared agreements about how people in the group will treat each other will help create the conditions for successful collaboration.

- What behaviors do you want to encourage?

- What behaviors that will not be tolerated?

- How is the team going to make decisions?

See examples in section 2.2.1

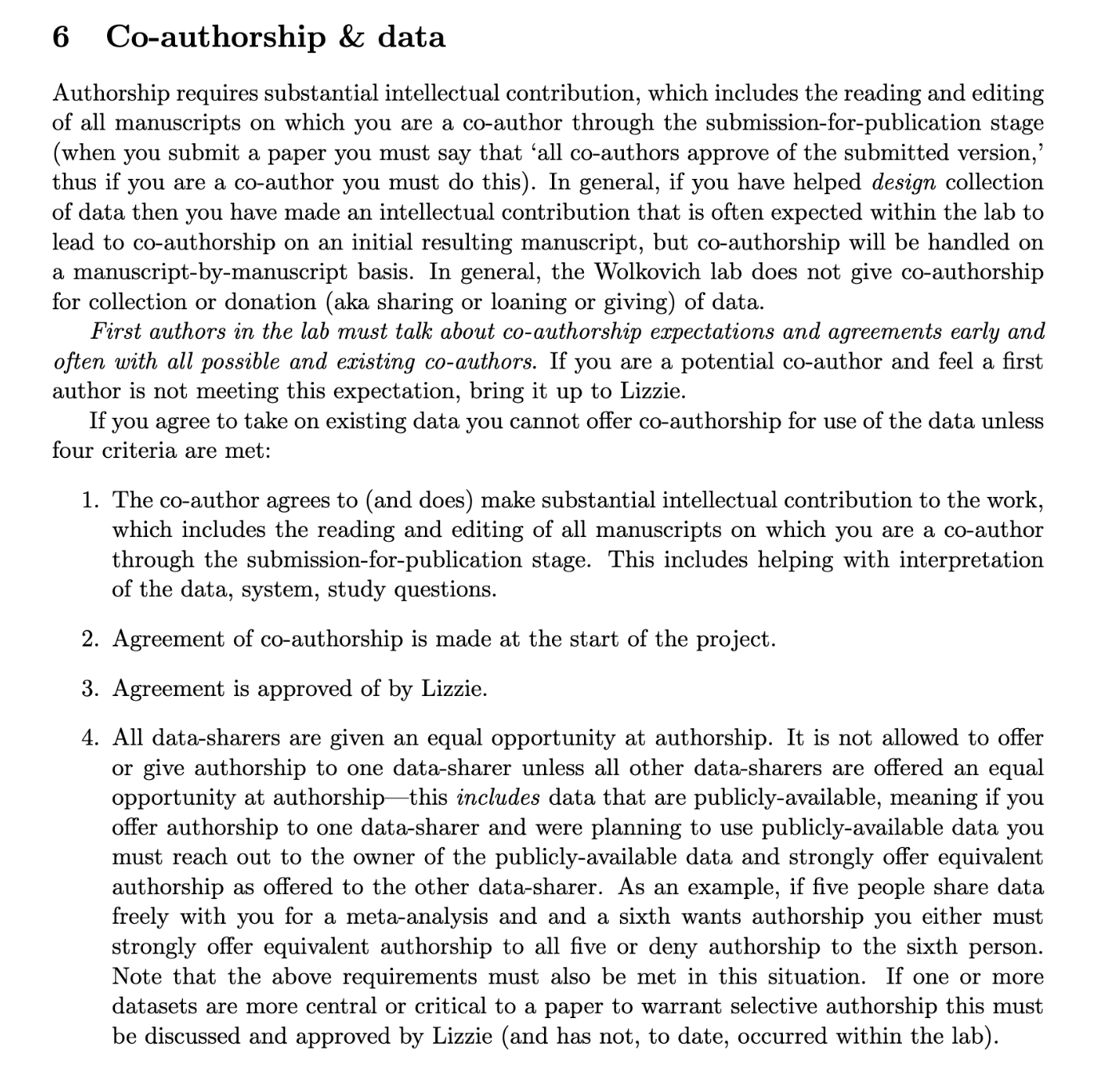

- Establishing Authorship and Credit Policies

- Check the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors guidelines for authorship and contribution

- Revise the NISO Contributor Roles Taxonomy (CRediT)

- As a group answer the following questions relevant questions to your project: What are our criteria for authorship? (See the ICMJE guidelines for potential criteria)

- Will we extend the opportunity for authorship to all group members on every paper or product?

- Do we want to have an opt in or opt out policy? (In an opt out policy, all group members are considered authors from the outset and must request removal from the paper if they don’t think they meet the criteria for authorship)

- Who has the authority to make decisions about authorship? Lead author? PI? Group?

- How will we decide authorship order?

- In what other ways will we acknowledge contributions and extend credit to collaborators?

- How will we resolve conflicts if they arise?

- Data Sharing and Reuse Policies

- Go over the Arctic Data Center Data Sharing and Reuse Policies Example template

- Use this template to start drafting a Data Sharing and Reuse Policies for your group.