6 Session 6: Collaboration Practices

6.1 Thinking preferences

6.1.1 Learning Objectives

An activity and discussion that will provide:

- Opportunity to get to know fellow participants and trainers

- An introduction to variation in thinking preferences

6.1.2 Thinking Preferences Activity

Step 1: Don’t jump ahead in this document. (Did I just jinx it?)

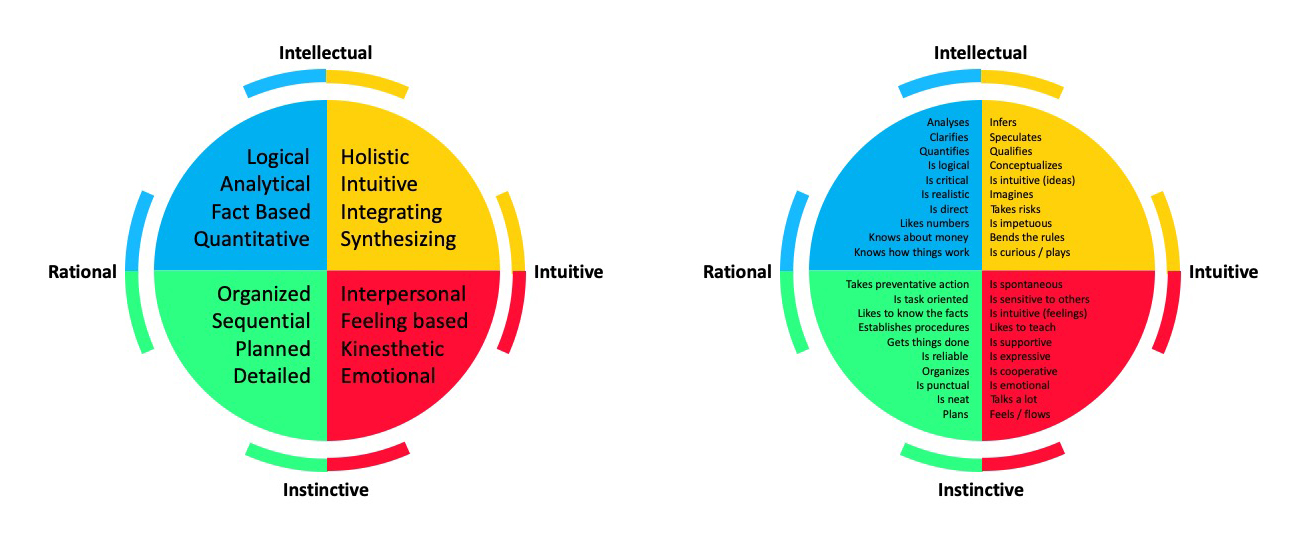

Step 2: Review the list of statements here and reflect on your traits. Do you learn through structured activities? Are you conscious of time and are punctual? Are you imaginative? Do you like to take risks? Determine the three statements that resonate most with you and record them. Note the symbol next to each of them.

Step 3: Review the symbol key here and assign a color to each of your three remaining statements. Which is your dominant color or are you a mix of three?

Step 4: Using the zoom breakout room feature, move between the five breakout rooms and talk to other participants about their dominant color statements. Keep moving until you cluster into a group of ‘like’ dominant colors. If you are a mix of three colors, find other participants that are also a mix.

Step 5: When the breakout rooms have reached stasis, each group should note the name and dominant color of your breakout room in slack.

Step 6: Take a moment to reflect on one of the statements you selected and share with others in your group. Why do you identify strongly with this trait? Can you provide an example that illustrates this in your life?

6.1.3 About the Whole Brain Thinking System

Everyone thinks differently. The way individuals think guides the way they work, and the way groups of individuals think guides how teams work. Understanding thinking preferences facilitates effective collaboration and team work.

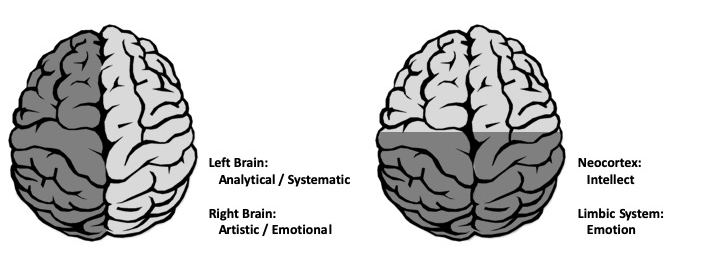

The Whole Brain Model, developed by Ned Herrmann, builds upon our understanding of brain functioning. For example, the left and right hemispheres are associated with different types of information processing and our neocortex and limbic system regulate different functions and behaviours.

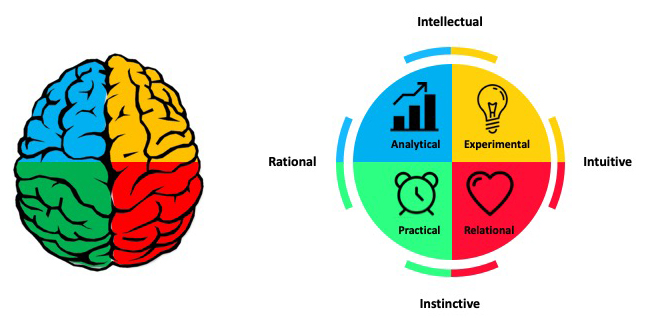

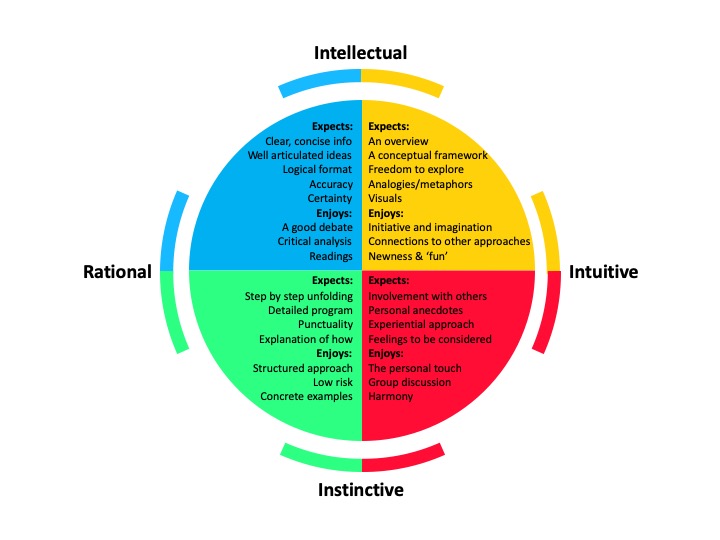

The Herrmann Brain Dominance Instrument (HBDI) provides insight into dominant characteristics based on thinking preferences. There are four major thinking styles that reflect the left cerebral, left limbic, right cerebral and right limbic.

- Analytical (Blue)

- Practical (Green)

- Relational (Red)

- Experimental (Yellow)

These four thinking styles are characterized by different traits. Those in the BLUE quadrant have a strong logical and rational side. They analyze information and may be technical in their approach to problems. They are interested in the ‘what’ of a situation. Those in the GREEN quadrant have a strong organizational and sequential side. They like to plan details and are methodical in their approach. They are interested in the ‘when’ of a situation. The RED quadrant includes those that are feelings-based in their apporach. They have strong interpersonal skills and are good communicators. They are interested in the ‘who’ of a situation. Those in the YELLOW quadrant are ideas people. They are imaginative, conceptual thinkers that explore outside the box. Yellows are interested in the ‘why’ of a situation.

Most of us identify with thinking styles in more than one quadrant and these different thinking preferences reflect a complex self made up of our rational, theoretical self; our ordered, safekeeping self; our emotional, interpersonal self; and our imaginitive, experimental self.

Undertsanding the complexity of how people think and process information helps us understand not only our own approach to problem solving, but also how individuals within a team can contribute. There is great value in diversity of thinking styles within collaborative teams, each type bringing stengths to different aspects of project development.

6.1.4 Bonus Activity: Your Complex Self

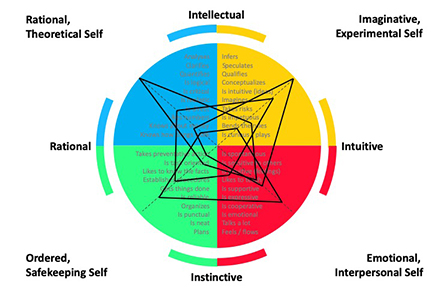

Using the statements contrained within this document, plot the quadrilateral representing your complex self.