15.1 The FAIR and CARE Principles

The idea behind these principles is to increase access and usage of complex and large datasets for innovation, discovery, and decision-making. This means making data available to machines, researchers, Indigenous communities, policy makers, and more.

With the need to improve the infrastructure supporting the reuse of data, a group of diverse stakeholders from academia, funding agencies, publishers and industry came together to jointly endorse measurable guidelines that enhance the reusability of data (Wilkinson et al. (2016)). These guidelines became what we now know as the FAIR Data Principles.

Following the discussion about FAIR and incorporating activities and feedback from the Indigenous Data Sovereignty network, the Global Indigenous Data Alliance developed the CARE principles (Carroll et al. (2021)). The CARE principles for Indigenous Data Governance complement the more data-centric approach of the FAIR principles, introducing social responsibility to open data management practices.

Together, these two principle encourage us to push open and other data movements to consider both people and purpose in their advocacy and pursuits. The goal is that researchers, stewards, and any users of data will be FAIR and CARE (Carroll et al. (2020)).

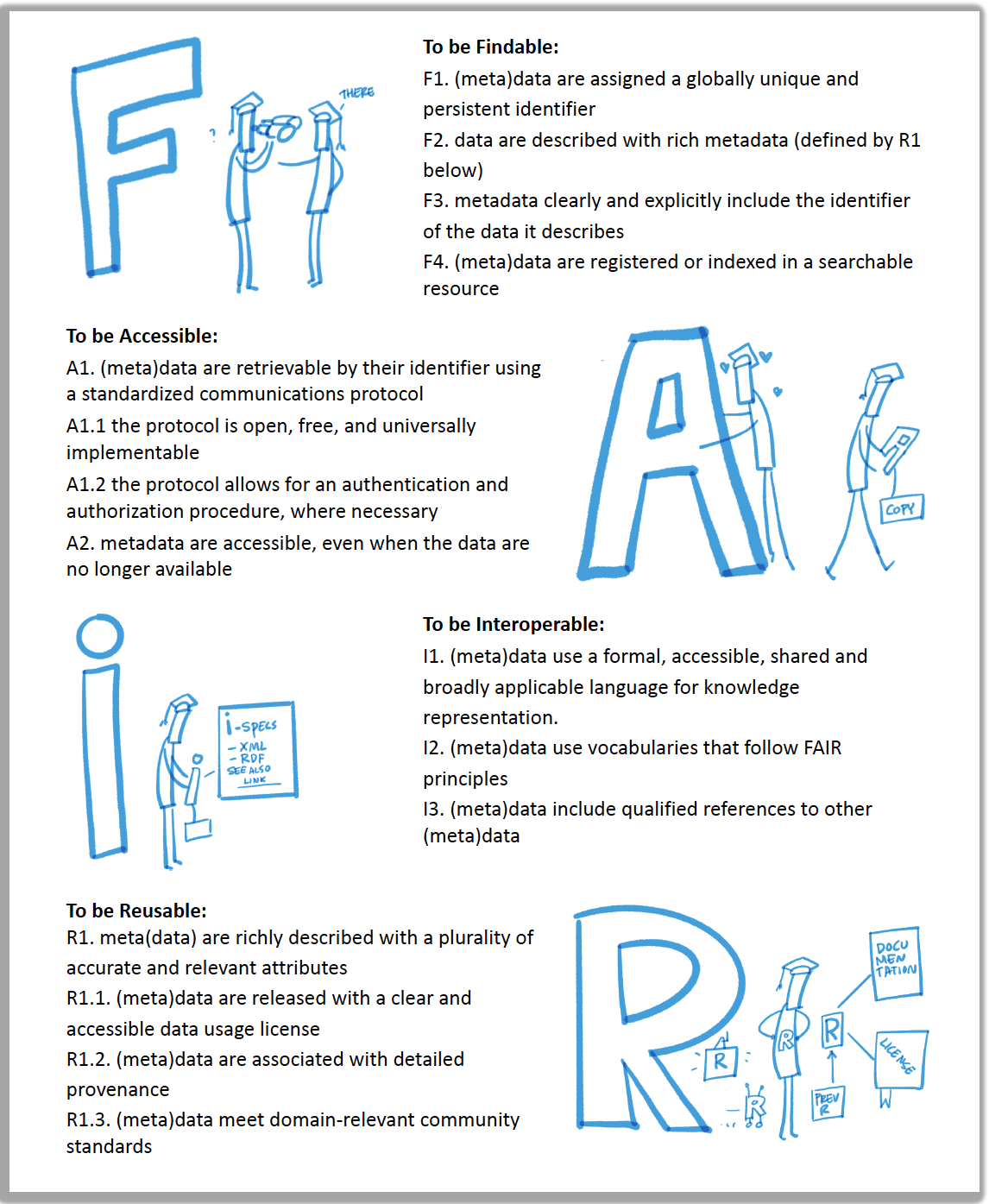

15.1.1 What is FAIR?

With the rise of open science and more accessible data, it is becoming increasingly important to address accessibility and openness in multiple ways. The FAIR principles focuses on how to prepare your data so that it can be reused by others (versus just open access of research outputs). In 2016, the data stewardship community published principles surrounding best practices for open data management, including FAIR. FAIR stands for Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reproducible. It is best to think about FAIR as a set of comprehensive standards for you to use while curating your data. And each principle of FAIR can be translated into a set of actions you can take during the entire lifecycle of research data management.

| FAIR | Definition |

|---|---|

| (F) Findable | Metadata and data should be easy to find for both humans and computers. |

| (A) Accessible | Once someone finds the required data, they need to know how the data can be accessed. |

| (I) Interoperable | The data needs to be easily integrated with other data for analysis, storage, and processing. |

| (R) Reusable | Data should be well-described so they can be reused and replicated in different settings. |

15.1.2 FAIR Principles in Practice

This is not an exhaustive list of actions for applying FAIR Principles to your research, but these are important big picture concepts you should always keep in mind. We’ll be going through the resources linked below so that you know how to use them in your own work.

- It’s all about the metadata. To make your data and research as findable and as accessible as possible, it’s crucial that you are providing rich metadata. This includes, using a field-specific metadata standard (i.e. EML or Ecological Metadata Language for earth and environmental sciences), adding a globally unique identifier (i.e. a Digital Object Identifier) to your datasets, and more. As discussed earlier, quality metadata goes a long way in making your data FAIR. One tool to help implement FAIR principles to non-FAIR data is the FAIRification process. This workflow was developed by GoFAIR, a self-governed initiative that aims to help implement the FAIR data principles.

- Assess the FAIRness of your research. The FAIR Principles are a lens to apply to your work. And it’s important to ask yourself questions about finding and accessing your data, about how machine-readable your datasets and metadata are, and how reusable it is throughout the entirety of your project. This means you should be re-evaluating the FAIRness of your work over and over again. One way to check the FAIRness of your work, is to use tools like FAIR-Aware and the FAIR Data Maturity Model. These tools are self-assessments and can be thought of as a checklists for FAIR and will provide guidance if you’re missing anything.

- Make FAIR decisions during the planning process. You can ensure FAIR Principles are going to implemented in your work by thinking about it and making FAIR decisions early on and throughout the data life cycle. As you document your data always keep in mind the FAIR lense.

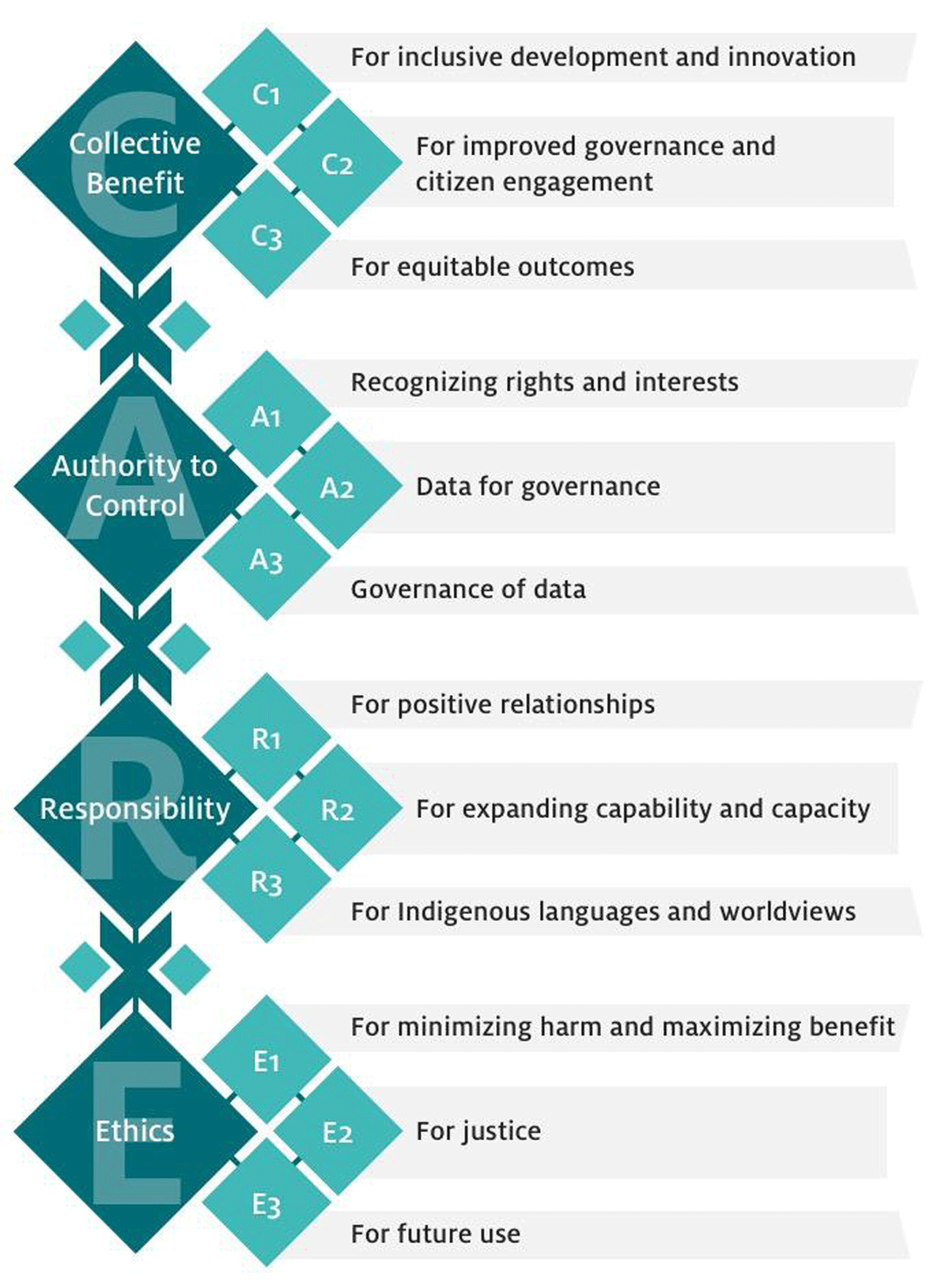

15.1.3 What is CARE?

The CARE Principles for Indigenous Data Governance were developed by the International Indigenous Data Sovereignty Interest Group in consultation with Indigenous Peoples, scholars, non-profit organizations, and governments (Carroll et al. (2020)). They address concerns related to the people and purpose of data. It advocates for greater Indigenous control and oversight in order to share data on Indigenous Peoples’ terms. These principles are people and purpose-oriented, reflecting the crucial role data have in advancing Indigenous innovation and self-determination. CARE stands for Collective benefits, Authority control, Responsibility and Ethics. It details that the use of Indigenous data should result in tangible benefits for Indigenous collectives through inclusive development and innovation, improved governance and citizen engagement, and result in equitable outcomes.

| CARE | Definition |

|---|---|

| (C) Collective Benefit | Data ecosystems shall be designed and function in ways that enable Indigenous Peoples to derive benefit from the data. |

| (A) Authority to Control | Indigenous Peoples’ rights and interests in Indigenous data must be recognized and their authority to control such data be empowered. Indigenous data governance enables Indigenous Peoples and governing bodies to determine how Indigenous Peoples, as well as Indigenous lands, territories, resources, knowledge and geographical indicators, are represented and identified within data. |

| (R) Responsibility | Those working with Indigenous data have a responsibility to share how those data are used to support Indigenous Peoples’ self-determination and collective benefit. Accountability requires meaningful and openly available evidence of these efforts and the benefits accruing to Indigenous Peoples. |

| (E) Ethics | Indigenous Peoples’ rights and well being should be the primary concern at all stages of the data life cycle and across the data ecosystem. |

15.1.4 CARE Principles in Practice

Make your data access to Indigenous groups. Much of the CARE Principles are about sharing and making data accessible to Indigenous Peoples. To do so, consider publish your data on Indigenous founded data repositories such as:

Use Traditional Knowledge (TK) and Biocultural (BC) Labels How do we think of intellectual property for Traditional and Biocultural Knowledge? Knowledge that outdates any intellectual property system. In many cases institution, organizations, outsiders hold the copy rights of this knowledge and data that comes from their lands, territories, waters and traditions. Traditional Knowledge and Biocultural Labels are digital tags that establish Indigenous cultural authority and governance over Indigenous data and collections by adding provenance information and contextual metadata (including community names), protocols, and permissions for access, use, and circulation. This way mark cultural authority so is recorded in a way that recognizes the inherent sovereignty that Indigenous communities have over knowledge. Giving Indigenous groups more control over their cultural material and guide users what an appropriate behavior looks like. A global initiative that support Indigenous communities with tools that attribute their cultural heritage is Local Contexts.

Assess the CAREness of your research. Like FAIR, CARE Principles are a lens to apply to your work. With CARE, it’s important to center human well-being in addition to open science and data sharing. To do this, reflect on how you’re giving access to Indigenous groups, on who your data impacts and the relationships you have with them, and the ethical concerns in your work. The Arctic Data Center, a data repository for Arctic research, now requires an Ethical Research Practices Statement when submitting data to them. They also have multiple guidelines on how to write and what to include in an Ethical Research Practices Statement.

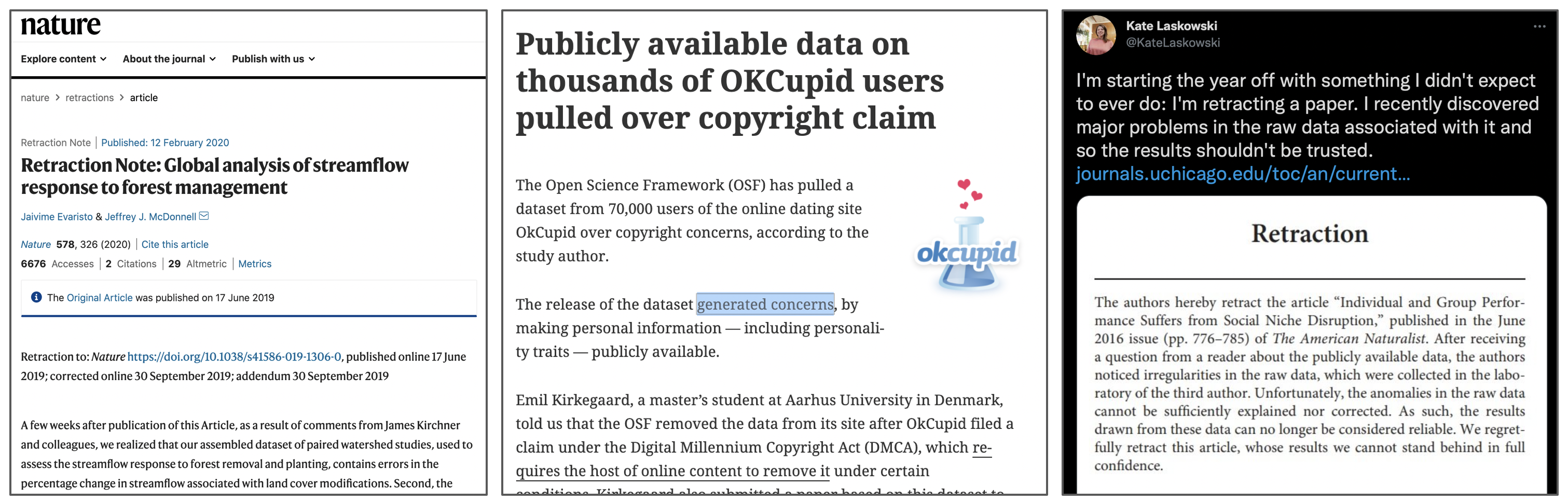

15.2 Research Data Publishing Ethics

For over 20 years, the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) has provided trusted guidance on ethical practices for scholarly publishing. The COPE guidelines have been broadly adopted by academic publishers across disciplines, and represent a common approach to identify, classify, and adjudicate potential breaches of ethics in publication such as authorship conflicts, peer review manipulation, and falsified findings, among many other areas. Despite these guidelines, there has been a lack of ethics standards, guidelines, or recommendations for data publications, even while some groups have begun to evaluate and act upon reported issues in data publication ethics.

To address this gap, the Force 11 Working Group on Research Data Publishing Ethics was formed as a collaboration among research data professionals and the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) “to develop industry-leading guidance and recommended best practices to support repositories, journal publishers, and institutions in handling the ethical responsibilities associated with publishing research data.” The group released the “Joint FORCE11 & COPE Research Data Publishing Ethics Working Group Recommendations” (Puebla, Lowenberg, and WG 2021), which outlines recommendations for four categories of potential data ethics issues:

- Authorship and Contribution Conflicts

- Authorship omissions

- Authorship ordering changes / conflicts

- Institutional investigation of author finds misconduct

- Legal/regulatory restrictions

- Copyright violation

- Insufficient rights for deposit

- Breaches of national privacy laws (GPDR, CCPA)

- Breaches of biosafety and biosecurity protocols

- Breaches of contract law governing data redistribution

- Risks of publication or release

- Risks to human subjects

- Lack of consent

- Breaches of himan rights

- Release of personally identifiable information (PII)

- Risks to species, ecosystems, historical sites

- Locations of endangered species or historical sites

- Risks to communities or societies

- Data harvested for profit or surveillance

- Breaches of data sovereignty

- Risks to human subjects

- Rigor of published data

- Unintentional errors in collection, calculation, display

- Un-interpretable data due to lack of adequate documentation

- Errors of of study design and inference

- Data manipulation or fabrication

Guidelines cover what actions need to be taken, depending on whether the data are already published or not, as well as who should be involved in decisions, who should be notified of actions, and when the public should be notified. The group has also published templates for use by publishers and repositories to announce the extent to which they plan to conform to the data ethics guidelines.

15.3 Exercise: Evaluate a Data Package on the EDI Repository

Explore data packages published on EDI assess the quality of their metadata. Imagine you’re a data curator!

- Break into groups and use the following data packages:

- Group A: EDI Data Portal SBC LTER: Reef: Abundance, size and fishing effort for California Spiny Lobster (Panulirus interruptus), ongoing since 2012

- Group B: EDI Data Portal Physiological stress of American pika (Ochotona princeps) and associated habitat characteristics for Niwot Ridge, 2018 - 2019

- Group C: EDI Data Portal Ecological and social interactions in urban parks: bird surveys in local parks in the central Arizona-Phoenix metropolitan area

You and your group will evaluate a data package for its: (1) metadata quality, (2) data documentation quality for reproducibility, and (3) FAIRness and CAREness.

- View our Data Package Assessment Rubric and make a copy of it to:

- Investigate the metadata in the provided data

- Does the metadata meet the standards we talked about? How so?

- If not, how would you improve the metadata based on the standards we talked about?

- Investigate the overall data documentation in the data package

- Is the documentation sufficient enough for reproducibility? Why or why not?

- If not, how would you improve the data documentation? What’s missing?

- Identify elements of FAIR and CARE

- Is it clear that the data package used a FAIR and CARE lens?

- If not, what documentation or considerations would you add?

- Investigate the metadata in the provided data

- Elect someone to share back to the group the following:

- How easy or challenging was it to find the metadata and other data documentation you were evaluating? Why or why not?

- What documentation stood out to you? What did you like or not like about it?

- How well did these data packages uphold FAIR and CARE Principles?

- Do you feel like you understand the research project enough to use the data yourself (aka reproducibility?)

If your group finishes early, check out more datasets in the bonus question.

15.4 Bonus: Investigate metadata and data documentation in other Data Repositories

Not all environmental data repositories document and publish datasets and data packages in the same way. Nor do they have the same submission requirements. It’s helpful to become familiar with metadata and data documentation jargon so it’s easier to identify the information you’re looking for. It’s also helpful for when you’re nearing the end of your project and are getting ready to publish your datasets.

Evaluate the following data packages at these data repositories:

- KNB Arthropod pitfall trap biomass captured (weekly) and pitfall biomass model predictions (daily) near Toolik Field Station, Alaska, summers 2012-2016

- DataOne USDA-NOAA NWS Daily Climatological Data

- Arctic Data Center Landscape evolution and adapting to change in ice-rich permafrost systems 2021-2022

How different are these data repositories from the EDI Data Portal? Would you consider publishing you data at one or multiple of these repositories?

:::